Memo to Justice Kennedy: Studies Show Pregnancy, Not Abortion, Creates Depression Risk for Women

Within the next six months, the United States Supreme Court may well overturn its 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling which recognized a woman's right to choose an abortion. In Whole Woman's Health v. Cole, the Court will decide whether the state of Texas has placed an "undue burden" on women's access to abortion services by requiring physicians to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital and by mandating that clinic facilities must meet the same standards as hospitals.

Whatever the decision in the majority opinion, it is virtually certain that the SCOTUS swing vote Justice Anthony Kennedy will write it. And that will be more than a little ironic. After all, Justice Kennedy has emerged as a one-man undue burden on Americans' reproductive rights, banning so-called "partial birth" abortion procedures in 2007 because of his personal belief that "some women come to regret their choice." As it turns out, recent studies show that pregnancy and birth--and not a mythical "post-abortion syndrome"--present the real depression risk for women.

That's the word from the United States Preventive Services Task Force. As the New York Times reported:

Women should be screened for depression during pregnancy and after giving birth, an influential government-appointed health panel said Tuesday, the first time it has recommended screening for maternal mental illness.

The recommendation, expected to galvanize many more health providers to provide screening, comes in the wake of new evidence that maternal mental illness is more common than previously thought; that many cases of what has been called postpartum depression actually start during pregnancy; and that left untreated, these mood disorders can be detrimental to the well-being of children.

It also follows growing efforts by states, medical organizations and health advocates to help women experiencing these symptoms -- an estimated one in seven postpartum mothers, some experts say.

The panel's recommendation comes just six months after the U.S. National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health published research showing that "more than 95 percent of participants reported that ending a pregnancy was the right decision for them." As ThinkProgress explained in July 2015, "Feelings of relief outweighed any negative emotions, even three years after the procedure":

Researchers examined both women who had first-trimester abortions and women who had procedures after that point (which are often characterized as "late-term abortions"). When it came to women's emotions following the abortion, or their opinions about whether or not it was the right choice, they didn't find any meaningful difference between the two groups.

These findings contradict the notion that women experience negative mental health effects after ending a pregnancy, as well as the idea that later abortions are more psychologically traumatic.

Contradict the notion, that is, that Anthony Kennedy put at the center of his 2007 majority opinion in Gonzales v. Carhart. Reversing the Court's position on so-called partial birth abortion just seven years after it struck down a similar Nebraska law, Kennedy swept away Justice Breyer's previous exception for "for the preservation of the...health of the mother." Derisively referring to physicians as "abortion doctors" and with callous disregard for the health of American women, Kennedy in the 5-4 majority opinion decreed that father knows best. (His 2000 dissent in Stenberg v. Carhart used the incendiary term "abortionist" no fewer than 13 times.) As the Washington Post's Ruth Marcus recalled:

"Respect for human life finds an ultimate expression in the bond of love the mother has for her child," Kennedy intoned. This is one of those sentences about women's essential natures that are invariably followed by an explanation of why the right at stake needs to be limited. For the woman's own good, of course.

Kennedy continues: "While we find no reliable data to measure the phenomenon, it seems unexceptionable to conclude some women come to regret their choice to abort the infant life they once created and sustained." No reliable data? No problem!

The State has "ethical and moral concerns that justify a special prohibition," Kennedy argued, because "it is self-evident that a mother who comes to regret her choice to abort must struggle with grief more anguished and sorrow more profound when she learns" the details of the abortion procedure.

As Marcus suggests, Kennedy's mantra of "no data, no problem" was never justifiable as a matter of either law or science, and to be sure, is no longer operative. Unfortunately, that came too late for the reproductive rights of American women.

As it turns out, the three-year longitudinal study published by NIH is just the latest in a mountain of research definitely debunking the "postabortion traumatic stress syndrome" myth that Kennedy codified in law. The new findings are a follow up to the "Turnaway Study" being conducted by the Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH) think-tank at the University of California, San Francisco. That project has been "following nearly 1,000 women who sought abortions in 21 different states."

The findings build on previous data from the ongoing Turnaway Study that's supported the same conclusions about mental health and abortion. In 2013, the researchers published the results from interviews conducted just one week after women had an abortion; at that point, too, the vast majority of women said they felt it was the right choice for them. The most common emotion they reported was relief.

In 2008, researchers at John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health evaluated 20 years of studies on the topic and reached a clear conclusion. As Robert Blum, the lead researcher put it, "The best research does not support the existence of a 'post-abortion syndrome' similar to post-traumatic stress disorder." Two years later, another study thoroughly demolished 2009 "research" which posited a link between abortion and subsequent mental health problems for women. Julia Steinberg of the University of California at San Francisco and Lawrence Finer of the Guttmacher Institute found that:

The findings of a 2009 study by Priscilla Coleman et al--which claimed that women who had reported an abortion were at an increased risk of several anxiety, mood and substance use disorders, compared with women who had never had an abortion--are not replicable.

Steinberg and Finer's analysis, just published online in Social Science & Medicine, examined the same dataset as Coleman et al. (the National Comorbidity Survey) and found that in every case, the proportions of women experiencing mental health problems reported by Coleman were much larger, sometimes more than five times as large, as Steinberg and Finer's results. The Coleman findings were also inconsistent with several other published studies using the same dataset and sample.

"We were unable to reproduce the most basic tabulations of Coleman and colleagues," Steinberg noted, concluding, "This suggests that their results are substantially inflated." And the Coleman findings, Steinberg pointed out, "were logically inconsistent with other published research."

Like the massive study from Johns Hopkins two years ago. That research reviewed 21 studies involving 150,000 women. The team's systematic analysis of the highest quality studies in terms of methodology showed "few, if any, differences between women who had abortions and their respective comparison groups in terms of mental health." In contrast, only the studies with "studies with the most flawed methodology" found any negative long-term, mental health impact.

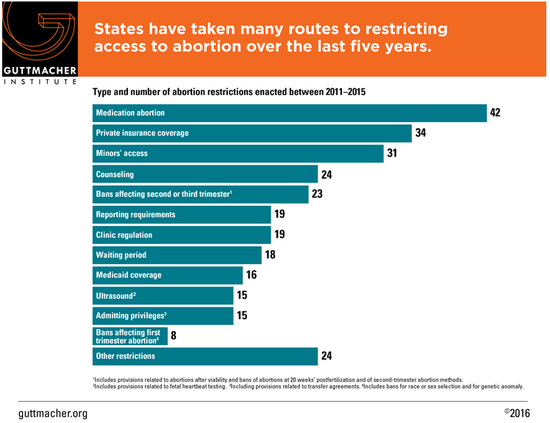

Nevertheless, Republicans in Congress and in the states continue to advance paternalistic abortion restrictions that ignore both the overwhelming consensus of scientists and the free speech rights of physicians. The party that declares its commitment to protecting "the doctor-patient relationship" instead mandates that physicians lie to their patients about what they know and what they don't know. Such government-ordered medical malpractice include state laws requiring medically unnecessary and shockingly invasive ultrasound procedures, mandating that doctors tell patients about mythical links to breast cancer and depression, preventing family planning providers from informing women about serious fetal genetic diseases and providing legal protections for not doing so. Other states laws have been telemedicine to discuss abortion procedures or to remotely administer drugs like RU-486. And in states like Iowa, conservative lawmakers are seeking to make so-called "abortion regret" grounds for civil action against providers:

Under the legislation, a patient could sue a doctor within ten years of terminating a pregnancy, even after signing a form acknowledging informed consent. In addition to suing for physical injury, a patient could sue for emotional distress, which would include a negative emotional or mental reaction, grief, anxiety, or worry.

The bill significantly increases the risk doctors face in providing abortion care in a couple of important ways. First and foremost, it creates an entirely separate legal claim related only to abortions, despite the fact that any patient injured during an abortion can already sue for medical malpractice. Second, it increases to at least ten years the amount of time a patient has to sue, and allows a claim to proceed even if a patient acknowledges that the risks associated with the procedure were explained.

Remember, that's coming from a Republican Party that routinely denounces "junk science" and the "jackpot justice" of malpractice lawsuits because, as President George W. Bush famously put it, "Too many OB/GYNs aren't able to practice their love with women all across this country." Besides, Justice Anthony Kennedy notwithstanding, those loving OB/GYNs are telling us, the real threat to women's emotional and mental health isn't abortion, but pregnancy.