Massachusetts Emergency Room Visits Fell after Health Care Reform

A new study in the journal Science revealed that emergency room use rose by 40 percent over 18 months among new Medicaid beneficiaries in Oregon starting in 2008. While opponents of Obamacare and its expansion of Medicaid cheered those findings suggesting that U.S. health care costs will go up as a result, their exhilaration may be premature. It's not just that the patterns of health care utilization by newly insured, lower income Americans could still be in flux after so short a period of time. As the Massachusetts experience suggests, after an initial spike ER use slowly dropped over time.

In March 2010, the Wall Street Journal trumpeted "The Failure of Romneycare." A central indictment of the 2006 Massachusetts health care reform that had slashed the ranks of the insured to just two percent while improving health of the newly covered was emergency room use:

The difficulties in getting primary care have led to an increasing number of patients who rely on emergency rooms for basic medical services. Emergency room visits jumped 7% between 2005 and 2007. Officials have determined that half of those added ER visits didn't actually require immediate treatment and could have been dealt with at a doctor's office--if patients could have found one.

But most (though not all) subsequent studies of the Massachusetts overhaul that served as the model for the Affordable Care Act found ER visits declined over time. In her 2012 assessment ("The Effect of Insurance on Emergency Room Visits: An Analysis of the 2006 Massachusetts Health Reform"), Sarah Miller reported an 8 percent decline in emergency department use over a period of several years. Her study followed a 2010 analysis by Jonathan T. Kolstad and Amanda E. Kowalski which found that Mitt Romney's reforms ultimately "affected utilization patterns by decreasing length of stay and the number of inpatient admissions originating from the emergency room." Examining data for hospital admissions originating from the emergency room, Kolstad and Kowalski found "a decline in inpatient admissions originating in the emergency room of 5.2 percent." While ER use by patients in wealthier ZIP codes was essentially unchanged:

We find that the reduction in emergency admissions was particularly pronounced among people from zip codes in the lowest income quartile [with an estimated] 12.2 percent reduction.

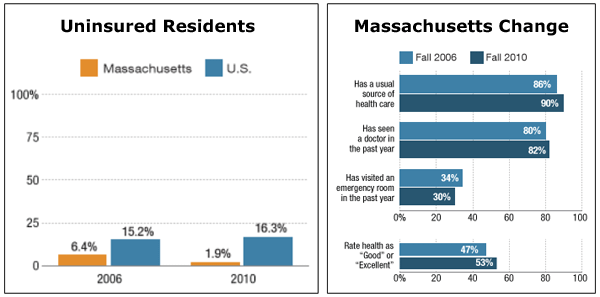

That conclusion echoed the findings of a January 2012 study ("Massachusetts Health Reforms: Uninsurance Remains Low, Self-Reported Health Status Improves As State Prepares To Tackle Costs") by Sharon K. Long, Karen Stockley, and Heather Dahlen. They found that a four percent decline in reported ER use between 2006 and 2010.

To be sure, none of the Massachusetts studies offered either the on-point design or the control group of those who did not receive Medicaid benefits that the new Harvard study of Oregon provided. And it's possible that Oregon's experience won't follow the Bay States trajectory. (The Washington Post's Sarah Kliff explains why it probably will.) If that's the case, ER use (roughly 4 percent of U.S. health costs) by the newly insured will increase and not decrease American health care spending. (It should be noted that in Republican states which rejected the Medicaid expansion, hospitals and red state taxpayers will have to foot the tab for uncompensated care by the still uninsured.) If that happens, Americans can take comfort in the studies which show, as the Obama administration rightly claims, "Medicaid saves lives and improves health outcomes."