10 Lessons from Bush's Fiasco in Iraq

"Obama lost Iraq." With the fall of Mosul and Tikrit to the forces of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIS), that will be the rallying cry for Republicans for the foreseeable future. Already, there is a chorus of voices from John McCain and the Wall Street Journal to right-wing radio and the conservative blogosphere charging that President Obama committed "the strategic blunder of leaving no U.S. forces in Iraq."

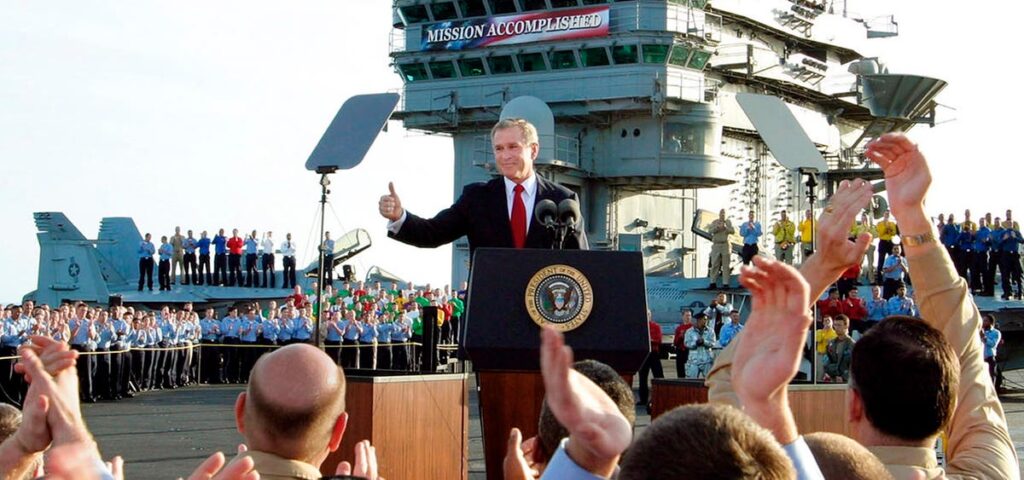

But foaming-at-the-mouth Republicans and their furious right-wing allies aren't just wrong. They are desperately trying to evade paternity for a world-historical calamity they birthed and still support. Iraq was lost the moment the first U.S. troops crossed the border from Kuwait. It's no surprise Republicans are running away from Bush's bastard. After all, there were no weapons of mass destruction. Saddam posed no imminent threat to the United States. There were not "ties going on between Al Qaeda and Saddam Hussein's regime." Americans were not "greeted as liberators" and victory was not "rapid, in about three weeks." The mission was not accomplished on May 1, 2003, and Ahmed Chalabi was not "a patriot who has the best interests of his country at heart." In 2005, the insurgency was nowhere near "its last throes." Meanwhile, it certainly was not the case, as John McCain claimed in April 2003 that "Nobody in Afghanistan threatens the United States of America."

In the run-up to the invasion of the Iraq, Secretary of State Colin Powell warned President Bush, "You break it, you own it." Eleven years later and five years after Dubya ambled out of the White House, Iraq remains broken and he owns it.

But that's not the only maxim George W. Bush and his allies should have learned from their debacle in Iraq. Here are 10 other lessons from Bush's Iraq disaster.

1. Don't Fight Wars on the Cheap

Going to war without the manpower needed to bring victory and secure the peace was one of the first things the Bush administration should have learned in Afghanistan. In December 2001, a lack of U.S. ground forces enabled the escape of Osama Bin Laden from the Tora Bora cave complex that should have been his burial ground. By March 2002, President Bush could only downplay the fiasco by declaring, "I just don't spend that much time on him .... I'll repeat what I said. I truly am not that concerned about him."

But by the beginning of 2003, Bush and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld were repeating their mistake, only on a much larger scale. That February top Army General Eric Shinseki warned Congress and the Bush administration that the American occupation of Iraq would require "something on the order of several hundred thousand soldiers." And for that honesty and prescience, General Shinseki was mocked and ridiculed. As Rumsfeld put it:

The idea that it would take several hundred thousand U.S. forces, I think, is far from the mark.

Rumsfeld's deputy Paul Wolfowitz was even more scathing. Wolfowitz, who just days after the invasion claimed "we're dealing with a country that could really finance its own reconstruction, and relatively soon," lambasted Shinseki at a hearing of the House Budget Committee:

Some of the higher-end predictions that we have been hearing recently, such as the notion that it will take several hundred thousand U.S. troops to provide stability in post-Saddam Iraq, are wildly off the mark.

When chaos erupted in Baghdad less than a month after the start of the U.S. invasion, Rumsfeld brushed it off: "Freedom's untidy, and free people are free to make mistakes and commit crimes and do bad things."

As it turned out, Shinseki was right. But it would take another four years until his wisdom was widely acknowledged. On January 10, 2007--the same day President Bush announced his "surge" to reverse the exploding civil war in Iraq--the New York Times reported, New Strategy Vindicates Ex-Army Chief Shinseki.

2. Don't Uncork Bottled Up Sectarian Divisions

The under-sized occupation force wasn't the only thing crisis Shinseki foresaw before President Bush began to "shock and awe." He also highlighted a key reason why a much larger American troop presence would be needed in post-Saddam Iraq:

We're talking about post-hostilities control over a piece of geography that's fairly significant with the kinds of ethnic tensions that could lead to other problems.

Problems, indeed. While Saddam Hussein and his Sunni minority regime had used brutality and foreign conflicts to keep the Shiite majority and Kurdish separatists under control, the carnage following the first Gulf War showed what Iraq's pent-up sectarian divisions could produce once unleashed. Behind closed doors, Secretary Rumsfeld admitted as much. In his famous October 15, 2002, "Parade of Horribles" memo, he fretted (briefly, to be sure) that "Iraq could experience ethnic strife among Sunni, Shia, and Kurds." As he put it in Point 17:

US could fail to manage post-Saddam Hussein Iraq successfully, with the result that it could fracture into two or three pieces, to the detriment of the Middle East and the benefit of Iran.

Within weeks of toppling Saddam, the United States was fighting former regime insurgents in the Sunni triangle, Shiite militias in Baghdad and Basra, and an influx of foreign Al Qaeda fighters in the west. The catastrophic disbanding of the Iraqi army and the draconian de-Baathification program carried out by L. Paul Bremer, viceroy of the Coalition Provisional Authority, made the dangerous situation more combustible.

Nevertheless, in August 2004 President Bush explained the growing U.S. casualties represented not the failure, but the success of the American invasion:

Had we had to do it [the invasion of Iraq] over again, we would look at the consequences of catastrophic success - being so successful so fast that an enemy that should have surrendered or been done in escaped and lived to fight another day.

Or as Vice President Dick Cheney put it almost two years before General David Petraeus led the U.S. surge, "I think they're in the last throes, if you will, of the insurgency."

Nine years after Cheney made that laughable statement, sectarian conflict has mushroomed across the Middle East. And as Dexter Filkins explained, the rise of ISIS in northwest Iraq can be attributed in large measure to the chaos across the border in Syria:

Iraq's collapse has been driven by three things. The first is the war in Syria, which has become, in its fourth bloody year, almost entirely sectarian, with the country's majority-Sunni opposition hijacked by extremists from groups like ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra, and by the more than seven thousand foreigners, many of them from the West, who have joined their ranks.

But as we'll see below, President Bush's man, Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki, made matters much, much worse.

3. Al Qaeda Thought It Was Better to Fight Us There

On October 14, 2003, President Bush announced that "we're making great progress in Iraq" before turning to a talking point he would use for years to come:

We'd rather fight them there than here.

As it turned out, Al Qaeda fighters across the Middle East and North Africa felt the same way.

Before he launched his war in Iraq, President Bush told the American people that Saddam's regime "has aided, trained and harbored terrorists, including operatives of al Qaeda." But after the administration's zombie lie about a mythical Saddam and Al Qaeda link was repeatedly debunked, Bush had to acknowledge in a December 2008 interview with Martha Raddatz of ABC News that it was the American presence that drew Al Qaeda fighters to Iraq, and not he reverse:

BUSH: One of the major theaters against al Qaeda turns out to have been Iraq. This is where al Qaeda said they were going to take their stand. This is where al Qaeda was hoping to take -

RADDATZ: But not until after the U.S. invaded.

BUSH: Yeah, that's right. So what? The point is that al Qaeda said they're going to take a stand. Well, first of all in the post-9/11 environment Saddam Hussein posed a threat. And then upon removal, al Qaeda decides to take a stand.

4. Sectarian U.S. Allies Can't Be Bought, Only Rented

In August 2006, the Washington Post reported, "Tribal sheikhs in Iraq's Anbar province turned against a chief U.S. threat: al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI)." General David Petraeus later described the so-called "Sunni Awakening," which began five months before President Bush announced the surge of thousands of additional U.S. troops into Iraq, as a turning point in the U.S.-led war effort. On January 5, 2007--five days before Bush addressed the nation about his surge strategy--John McCain agreed with that assessment:

Too often the light at the tunnel has turned out to be a train, but I really believe -- I really believe that there's a strong possibility that you may see a very substantial change in Anbar province due to this new changes in our relationships with the sheiks in the region.

But the decision of Sheik Ahmed Abu Risha and other Sunni tribal leaders to turn on the Al Qaeda forces led by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and partner with the U.S. in arming some 90,000 Sons of Iraq came with a big asterisk attached. As the Post noted in 2008:

But experts stress the moves by Sunni sheikhs was less an embrace of U.S. objectives and more a repudiation of al-Qaeda in Iraq's actions...

"The Americans think they have purchased Sunni loyalty," Nir Rosen, a fellow at New York University Center on Law and Security, told Congress in April 2008. "But in fact it is the Sunnis who have bought the Americans" by buying time to challenge the Shiite government.

By late 2007, there were already worries that the Sunnis wouldn't stay bought, with Shiite politicians and CIA analysts warning that "when the U.S. leaves, what we'll have are two armies" and "there is a danger here that we are going to have armed all three sides: the Kurds in the north, the Shiite and now the Sunni militias." And that risk would be elevated if the Shiite-controlled government led by Prime Minister Al-Maliki refused to accommodate Sunni interests in Baghdad. And, as the New York Times warned as the last American troops were leaving Iraq in December 2011, that fear was being realized:

The Shiite-dominated central government has arrested prominent Sunnis on accusations that they are secret members of the long-disbanded Baath Party, which has alienated Sunni elites. Meanwhile, a Sunni revolt a few hundred miles to the north of here against the Shiite-aligned government in neighboring Syria is gathering force.

Last month, government police officers wounded two guards and detained two others in a raid on the home of a Sunni, Sheik Albo Baz, in Salahuddin Province, prompting a protest by several thousand Sunnis in Samarra, a city divided by sect.

This followed the roundup by police officers of 600 suspected Baath Party sympathizers in October; they were accused of planning a coup.

For the moment, Abu Risha and many of the Sunni tribal leaders remain allied with the central government in Baghdad. But as the attacks from ISIS intensified, many of their Sons of Iraq did not. Many Sunni members of the Iraqi army simply walked away.

5. Don't Hitch the U.S. Wagon to the Wrong Strongman

That's why, as Fred Kaplan put it, "The collapse of Mosul, Iraq's second-largest city, has little to do with the withdrawal of American troops and everything to do with the political failure of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki." It was, after all, Maliki who refused to sign a permanent status of forces agreement with the U.S. It was Maliki who cracked down on Sunni opponents and put the tenuous relationship with the tribal sheikhs at risk. And Nouri Al-Maliki was George Bush's man in Baghdad.

Writing in the New Yorker, Dexter Filkins recalled Maliki's ascension to the premiership engineered by the Bush administration. In 2006, Bush undermined the incumbent PM, Ibrahim al-Jaafari, who struggling to form a government:

An avuncular, bookish figure, Jaafari had infuriated Bush with his indecisiveness, amiably presiding over the sectarian bloodbath that had followed the recent bombing of a major Shiite shrine

During the videoconference, Bush asked Khalilzad, "Can you get rid of Jaafari?"

"Yes," Khalilzad replied, "but it will be difficult."

Difficult, but not impossible. "I have a name for you," a CIA offered told U.S. Ambassador to Iraq Zalmay Khalilzad, "Maliki."

And as Filkins explained this week, "Maliki is a militant sectarian to the core, and he had been fighting on behalf of Iraq's long-suppressed Shiite majority for years before the Americans arrived, in 2003." That also explains in part why John McCain and Lindsey Graham urged President Bush in September 2008 to engineer a coup against Maliki. That's why Filkins, who believes the U.S. should have tried harder to maintain a small legacy force in place, believes Al-Maliki is "probably the dominant" factor in the current disintegration in Iraq:

Time and again, American commanders have told me, they stepped in front of Maliki to stop him from acting brutally and arbitrarily toward Iraq's Sunni minority. Then the Americans left, removing the last restraints on Maliki's sectarian and authoritarian tendencies.

In the two and a half years since the Americans' departure, Maliki has centralized power within his own circle, cut the Sunnis out of political power, and unleashed a wave of arrests and repression. Maliki's march to authoritarian rule has fueled the reëmergence of the Sunni insurgency directly. With nowhere else to go, Iraq's Sunnis are turning, once again, to the extremists to protect them.

That was evident in rapid ISIS takeover of Mosul. The much larger Iraqi army units evaporated in the face of hundreds of ISIS fighters. On Thursday, the Washington Post described the reaction of residents:

For many in the mostly Sunni city, the ouster of the hated national security forces was welcome, offering a sign of just how much the Shiite-dominated government in Baghdad has alienated the Sunni population in the eight years since Maliki came to power.

With his declaration of emergency coming just two weeks after a disputed and inconclusive election, Prime Minister Al-Maliki will likely seek to consolidate his power further still. Such a development could only make the Sunni alienation worse.

It's worth remembering that Nouri Al-Maliki wasn't George W. Bush's first choice to head up the post-Saddam government in Baghdad. That honor was bestowed on Ahmed Chalabi, the exiled swindler-turned-face of the Iraqi National Congress. By 2006, Chalabi was being sought by U.S. forces in Iraq for spying on behalf of Tehran. But in 2004, he was President Bush's guest at the State of the Union address. As John McCain described Chalabi the year before, "He's a patriot who has the best interests of his country at heart."

6. The Enemy of Our Enemy is Not Our Friend

If there was any question that the blowback from George W. Bush's invasion of Iraq only served to produce an Iranian ally in Baghdad, the final, humiliating proof came in January. As the radical ISIS forces already disowned by Al Qaeda swept from Syria into Fallajuh and Ramadi, adding to the chaos, Iran like the United States offered to provide military aid to the al-Maliki government. In acknowledging the irony of overlapping Iranian and American interests in seeing the defeat of ISIS AL Qaeda fighters in Syria and Iraq, Iranian reform politician Mashallah Shamsolvaezin declared:

We face the same enemy, and the enemy of my enemy is my friend.

Five months later, U.S. surveillance aircraft are monitoring Iraq as President Obama weighs additional assistance and possible American air strikes against ISIS forces. Meanwhile, the Wall Street Journal on Thursday reported that Iran had already dispatched two Revolutionary Guards units to help defend Baghdad and protect the Shiite shrine cities of Najaf and Karbala.

If that assistance for Al-Maliki in Baghdad sounds familiar, it should. Because it was the influx of Shiite fighters from Iran and Hezbollah in Lebanon that helped the Allawi President Bashar Al-Assad reverse the civil war in Syria. And while the Iranian-allied forces helped Assad batter the Free Syrian Army backed by the United States, the Sunni forces of ISIS renounced by Al Qaeda were pounding the western-supported rebels as well.

To put it another way, in Iraq the enemy of our enemy is the friend of our friend. But that doesn't make Iran our friend: across the border in Syria, Iran is the friend of our enemy.

All of which brings us back to Lesson 2 ("Don't Uncork Bottled Up Sectarian Divisions") above. It's awfully hard to distinguish friend from foe in the Middle East if you, like John McCain, can't remember the difference between Shiite and Sunni. Just as dangerous is to pretend, as Weekly Standard editor and Project for the New American Century (PNAC) Iraq war cheerleader Bill Kristol did in 2003, that sectarian divisions don't exist at all:

On this issue of the Shia in Iraq, I think there's been a certain amount of, frankly, a kind of pop sociology in America that, you know, somehow the Shia can't get along with the Sunni and the Shia in Iraq just want to establish some kind of Islamic fundamentalist regime. There's almost no evidence of that at all. Iraq's always been very secular.

7. U.S. Forces Should Never Be Deployed Permanently in a Civil War Zone

Reacting to the current chaos in Iraq, John McCain on Thursday had only praise for himself:

"Lindsey Graham and John McCain were right," McCain said. "Our failure to leave forces on Iraq is why Sen. Graham and I predicted this would happen."

Of course, McCain has been wrong about almost everything in Iraq from the get-go. But his insistence on permanently keeping American troops and materiel in Iraq is based on a very flawed analogy. As he put it in June 2008:

Americans are in South Korea, Americans are in Japan, American troops are in Germany. That's all fine.

When The Nation reporter David Corn asked McCain about his earlier suggestion that American forces could remain in Iraq for a hundred years, "he reaffirmed the remark, excitedly declaring that U.S. troops could be in Iraq for 'a thousand years' or 'a million years,' as far as he was concerned."

But Iraq is not Germany, Japan and South Korea. In each of those cases, U.S. forces maintain permanent bases to protect the host government from external threats, project American power in the region and to deter potential Russian (previously Soviet), Chinese and North Korea aggression. In Iraq, the U.S. became embroiled in a sectarian civil war that ultimately cost 4,500 American lives and wounded over 30,000 more. There is no place on earth where the United States maintains a permanent military presence to prevent communal violence or tip the scales in a civil war.

Perhaps the most pathetic thing is that John McCain knew this maxim once. Twenty years before the Iraq War and 30 before he called for American intervention in Syria, McCain opposed President Reagan's 1983 peace-keeping mission in Lebanon. As CNN recalled in 2008:

McCain said "I do not see any obtainable objectives in Lebanon" and that "the longer we stay there, the harder it will be to leave." On Oct. 23, 1983, a suicide attack at the Marine headquarters in Beirut killed 241 U.S. service members.

"In Lebanon, I stood up to President Reagan, my hero, and said, if we send Marines in there, how can we possibly beneficially affect this situation? And said we shouldn't. Unfortunately, almost 300 brave young Marines were killed." McCain said at the debate.

8. Regime Change is a Recipe for Disaster

A Republican presidential debate in December 2011 provided one of the most telling moments of the entire campaign. One after another, the GOP candidates described the Iranian nuclear program as an imminent, existential threat to the United States that cannot be allowed to come to fruition. Then-frontrunner Newt Gingrich explained how he would handle Tehran and its nuclear ambitions:

I think replacing the regime before they get a nuclear weapon without a war beats replacing the regime with war, which beats allowing them to have a nuclear weapon. Those are your three choices.

Gingrich made that pronouncement, even as the last U.S. troops were preparing the leave Iraq, a place where 4,500 Americans were killed and a trillion dollars squandered. And all of that sacrifice came in the name of "regime change."

A quick spin through the Wayback Machine can dredge up the infamous letter from the Project for a New American Century to President Clinton in 1998. Signed by what now looks like many future inhabitants of Dante's inner circle, Bill Kristol, John Bolton, Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz, Elliott Abrams among others urged a replacement for the containment policy that had kept Saddam Hussein in a stranglehold:

In your upcoming State of the Union Address, you have an opportunity to chart a clear and determined course for meeting this threat. We urge you to seize that opportunity, and to enunciate a new strategy that would secure the interests of the U.S. and our friends and allies around the world. That strategy should aim, above all, at the removal of Saddam Hussein's regime from power. We stand ready to offer our full support in this difficult but necessary endeavor...

In the near term, this means a willingness to undertake military action as diplomacy is clearly failing. In the long term, it means removing Saddam Hussein and his regime from power. That now needs to become the aim of American foreign policy.

We all know how that policy, made real by the administration of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney, worked out. Replacing governments, especially by military force, has not generally been a happy experience for the United States. As for those still advocating regime change as a goal of American foreign policy, be careful what you ask for. You might just get it.

9. Democracy Promotion Can't Come from the Barrel of Gun

During its short but incredibly damaging life, the Bush Doctrine advocated three propositions. The first was that the United States would not tolerate safe havens for terrorists, a pledge belied by President Bush's refusal to launch unilateral American strikes to take out Osama Bin Laden and high-ranking Al Qaeda targets inside Pakistan.

The second pillar of the Bush Doctrine was democracy promotion. As he put it in his 2005 State of the Union address, Bush declared that the mission of the United States was nothing less than to end tyranny and dictatorship worldwide:

The only force powerful enough to stop the rise of tyranny and terror, and replace hatred with hope, is the force of human freedom...And we've declared our own intention: America will stand with the allies of freedom to support democratic movements in the Middle East and beyond, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.

Predictably, the neoconservative amen corner collectively chanted its approval. David Brooks proclaimed "the Bush agenda is dominating the globe." On March 4, 2005, Charles Krauthammer declared, "We are at the dawn of a glorious, delicate, revolutionary moment in the Middle East," adding "It is our principles that brought us to this moment by way of Afghanistan and Iraq." Three days later in a Time piece titled Three Cheers for the Bush Doctrine, Krauthammer mocked the opponents of the Bush Doctrine vision of democratic transformation in the Middle East, labeling them "embarrassingly, scandalously, blessedly wrong." And the next day, the National Review's Rich Lowry proclaimed, "By toppling Saddam Hussein and insisting on elections in Iraq, while emphasizing the power of freedom, Bush has put the United States in the right position to encourage and take advantage of democratic irruptions in the region."

But it was Kristol of the Weekly Standard who was perhaps the Bush Doctrine's most vocal cheerleader and self-satisfied proponent. In the wake of the Iraqi elections, Kristol declared the complete victory of the Bush Doctrine and the arrival of a seminal moment in world history, one ushering in a new era of democratic change around the globe:

Just four weeks after the Iraqi election of January 30, 2005, it seems increasingly likely that that date will turn out to have been a genuine turning point. The fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, ended an era. September 11, 2001, ended an interregnum. In the new era in which we now live, 1/30/05 could be a key moment--perhaps the key moment so far--in vindicating the Bush Doctrine as the right response to 9/11. And now there is the prospect of further and accelerating progress.

But things didn't work out that way. The elation of purple fingers in Iraq, the Orange Revolution in Ukraine and the Cedar Revolution in Lebanon soon faded. Iraq descended deeper into civil war. Hamas won the Palestinian elections in 2006. When the Arab Spring arrived, it came as a response to corrupt authoritarian rule. And it wasn't led by U.S. force or even American ideals, as the revolution triggered by a fruit vendor in Tunis showed. And when Egypt replaced Hosni Mubarak with a freely elected Muslim Brotherhood government, the neocons were horrified by the Frankenstein democracy they helped engineer.

10. Preventive War is an Idea Whose Time Has Never Come

The third and most controversial tenet of the Bush Doctrine was preventive war.

Whether or not preventive war constitutes legitimate self-defense under international law, history is replete with examples. (For Americans, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor should leap to mind.) While "pre-emption" is "meant to grab the tactical advantages of striking first against what is seen as a truly imminent threat, when an adversary's attack is close at hand," in contrast the Oxford Bibliographies explained:

The strategic logic of preventive war is rooted in the desire to halt the erosion of relative power to a rising adversary and the future dangers this power shift might present. Leaders calculate that a war fought in the near term will be less costly than a war fought at a later date, after the potential adversary has had an opportunity to increase its military capabilities. Under preventive war conditions, there is no certainty that this future war will actually be fought; preventive war is launched to avoid the mere possibility of a higher-cost future war or the potential for the target state to use its rising power in a coercive way.

To be sure, President Bush's invasion of Iraq was an exercise in preventive war. In his October 7, 2002, address in Cincinnati, Bush warned, "Facing clear evidence of peril, we cannot wait for the final proof--the smoking gun--that could come in the form of a mushroom cloud." That echoed the talking point National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice mouthed a month earlier, when she fretted, "We don't want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud." Addressing the Veterans of Foreign Wwars nearly six months before Colin Powell would make his infamous presentation to the United Nations, Vice President Dick Cheney was unequivocal about the future threat from Saddam Hussein:

Simply stated, there is no doubt that Saddam Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction. There is no doubt he is amassing them to use against our friends, against our allies, and against us. And there is no doubt that his aggressive regional ambitions will lead him into future confrontations with his neighbors -- confrontations that will involve both the weapons he has today, and the ones he will continue to develop with his oil wealth.

For his part, John McCain was on board 100 percent. He didn't just agree that the Iraq war would be a short one and that Americans would be "greeted as liberators." Three months after the invasion in June 2003, McCain announced:

I remain confident that we will find weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.

But it didn't work out that way. Bush, Cheney, Rice and McCain (among others) were, as Iraq Survey Group Charles Duelfer testified in October 2004, "almost all wrong." And not just about WMD, but about Saddam's links to Al Qaeda and pretty much everything else. To have any legitimacy in international law and in the court of world opinion, the justifications for preventive war must be true and the "gathering threats" real ones. The Bush administration failed on every criterion.

To put it another way, if any idea should have been thoroughly discredited by the blood and treasure lost in ousting Saddam Hussein and the subsequent carnage in Iraq, it is the very notion of preventive war itself.

Nevertheless, if the Republicans now attacking President Obama have their way, the United States will be on a course for a new preventive war, this time against Iran. But if the negotiations with Tehran over its nuclear program falter, President Obama will have to ask himself the same challenges he issued two years ago. As Obama cautioned in March 2012, "This is not a game," he said. "And there's nothing casual about it."

If some of these folks think that it's time to launch a war, they should say so. And they should explain to the American people exactly why they would do that and what the consequences would be.

Or as General David Petraeus put it during the run-up to the invasion of Iraq, "Tell me how this ends."

The final ending hasn't been written yet. But we do know this: President George W. Bush broke Iraq. And his legacy, now and forever, is that he owns it.