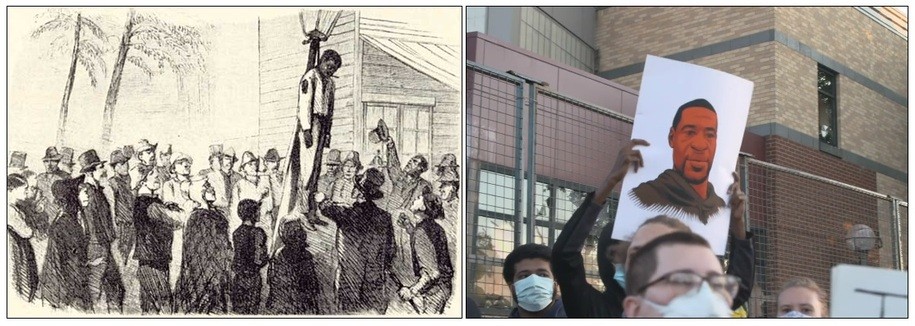

There were probably not less than a dozen negroes beaten to death in different parts of the City during the day. Among the most diabolical of these outrages that have come to our knowledge is that of a negro cartman living in Carmine-street. About 8 o'clock in the evening as he was coming out of the stable, after having put up his horses, he was attacked by a crowd of about 400 men and boys, who beat him with clubs and paving-stones till he was lifeless, and then hung him to a tree opposite the burying-ground. Not being yet satisfied with their devilish work, they set fire to his clothes and danced and yelled and swore their horrid oaths around his burning corpse. The charred body of the poor victim was still hanging upon the tree at a late hour last evening.

That victim had a name. He was Abraham Franklin, a disabled man who worked as a coachman. As they hung him from a lamppost, his killers cheered for Jefferson Davis. That would be the same Jefferson Davis who after assuming the Presidency of the Confederate States of America in 1861 explained the South’s cause to his people:

“We recognized the negro as God and God's Book and God's laws, in nature, tell us to recognize him. Our inferior, fitted expressly for servitude.”

But it wasn’t just Jefferson’s fellow traitors who recognized “the fact of the inferiority stamped upon that race by the Creator, and from cradle to grave, our government, as a civil institution, marks that inferiority." Outside of the ranks of the most fervent abolitionists, the deeply embedded racism of white Americans in the North similarly took for granted their own racial superiority. In the abomination that was its 7-2 decision in the 1857 case of Dred Scott v. Sandford, the Supreme Court concluded that even long-time residence in a free state or territory did not afford the slave protection from re-enslavement afterwards. As Justice Roger Taney proclaimed in his infamous opinion, African Americans were not and could never be citizens of the United States:

They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect, and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.

To be sure, the Dred Scott decision and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 produced wide-spread revulsion in the northern states. Nevertheless, abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison still found themselves occupying a minority position even in the aftermath to those twin blows to their fight against slavery. For as long as it persisted, his friend and ally Frederick Douglass warned him in an 1846 letter, nothing about the natural majesty of the United States or the American project itself could clean away the hypocritical sin of slavery.

But my rapture is soon checked, my joy is soon turned to mourning. When I remember that all is cursed with the infernal spirit of slaveholding, robbery and wrong,— when I remember that with the waters of her noblest rivers, the tears of my brethren are borne to the ocean, disregarded and forgotten, and that her most fertile fields drink daily of the warm blood of my outraged sisters, I am filled with unutterable loathing, and led to reproach myself that any thing could fall from my lips in praise of such a land.

When Frederick Douglass asked in 1852, “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?” his was the accusation of a true American patriot demanding national accountability in keeping with the promises of the country’s founding documents.

For his part, Abraham Lincoln was doubtless in agreement with his future friend. In 1855, Lincoln wrote to his Joshua Speed to reject the “Know Nothings,” the “America Firsters” of their day.

Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that "all men are created equal." We now practically read it "all men are created equal, except negroes." When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read "all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics." When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty -- to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocracy [sic].

Still, as President Lincoln distinguished between his “official duty” and “my oft-expressed personal wish that all men every where could be free.” Even as he was just weeks away from issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln explained to New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley on August 22, 1862:

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.

(It is with good reason that Frederick Douglass eulogized the 16th President in this way at the 1876 unveiling of the Freedmen’s Monument: “Viewed from the genuine abolition ground, Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined.”)

But as Lincoln explained to Congress on December 1, 1862, “As our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.”

“In giving freedom to the slave we assure freedom to the free--honorable alike in what we give and what we preserve. We shall nobly save or meanly lose the last best hope of earth.”

And with the promise of emancipation made, it had to be kept. Lincoln did not waiver in his commitment at Gettysburg to a "new birth of freedom" even as he endured the darkest days of the Civil War in the summer of 1864. With Grant stalemated in front of Petersburg and Sherman halted at Atlanta after the brutal fighting that spring and summer, Lincoln's reelection seemed an impossibility. But when Northern War Democrats and some in his own party were urging him to abandon the emancipation of the slaves, Lincoln was having none of it.

"I am sure you will not, on due reflection, say the promise being made must be broken at the first opportunity...As a matter of morals, could such treachery escape the curses of Heaven or any good man? As a matter of policy, to announce such a purpose would ruin the Union cause itself. All recruiting of colored men would cease and all colored men now in our service would instantly desert us. And rightfully too. Why should they give their lives for us, with our full notice of our purpose to betray them?"

Were he to return black soldiers to slavery, Lincoln declared, "I should be damned in time and eternity."

And rightly so. Throughout the spring and summer of 1863, Lincoln had urged the deployment of black troops. “If they stake their lives for us, they must be prompted by the strongest motive—even the promise of freedom,” Lincoln said, “And the promise being made, must be kept.” Noting reports from some of his commanders that "the emancipation policy, and use of colored troops, constitute the heaviest blow yet dealt to the rebellion," Lincoln reminded his critics in August 1863:

"You say you will not fight to free the negroes. Some of them seem willing to fight for you."

By the end of the war, that “some” numbered a staggering 200,000. There has never been a time in the 400 years since the first settlement of white Europeans in what would become the United States that blacks were not themselves the driving agents of their own liberation (and, therefore all Americans). In his March 21, 1863 editorial, “Men of Color: To Arms!” Frederick Douglass challenged blacks North and South:

Liberty won by white men would lose half its luster. "Who would be free themselves must strike the blow." "Better even die free, than to live slaves." This is the sentiment of every brave colored man amongst us.

“Very well, let the white fight for what the[y] want and we negroes fight for what we want,” one who heard Douglass’ call answered, “Liberty must take the day; nothing shorter.” On July 22, 1863, a convention of black Americans held in Poughkeepsie, New York resolved:

That more effective remedies ought now to be thoroughly tried, in the shape of warm lead and cold steel, duly administered by 200,000 black doctors…

We should strike, and strike hard, to win a place in history, not as vassals, but as men and heroes, never forgetting that God, as ever, strikes for the right, ever helping those most who help themselves.

Black Americans did free themselves and, as a result, made possible the ongoing project to bring freedom and equality to all Americans for all time. But sadly, liberty did not “take the day.” White supremacy in the South, aided by a complicit Supreme Court and exhaustion and racism in the North, fueled the imposition of Jim Crow across the former Confederate states. Anti-immigrant fervor in the 1920’s made the prevailing white racism worse, as reflected in the strength of the Ku Klux Klan in the states like New Jersey, Ohio and Illinois.

That’s what made the August 28, 1963 “Dream Speech” by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. simultaneously so inspirational and so heartbreaking. One hundred years after Abraham Franklin was butchered in New York, King like Douglass and Lincoln before him simply asked Americans to live up to the ideals proclaimed by the Declaration of Independence.

“I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”

Only two months earlier, President John F. Kennedy on June 11 addressed the nation on the need for new civil rights laws on the same day National Guard troops ensured the entry of two black students into the University of Alabama. Until this nationally televised address, Douglass probably have considered JFK like Lincoln “tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent.”) Noting that the nation was facing an issue that was neither sectional nor partisan, Kennedy warned, “Difficulties over segregation and discrimination exist in every city, in every State of the Union, producing in many cities a rising tide of discontent that threatens the public safety.”

We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution.

The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities, whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated. If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, if he cannot send his children to the best public school available, if he cannot vote for the public officials who will represent him, if, in short, he cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in his place? Who among us would then be content with the counsels of patience and delay?

One hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free. They are not yet freed from the bonds of injustice. They are not yet freed from social and economic oppression. And this Nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free.

We preach freedom around the world, and we mean it, and we cherish our freedom here at home, but are we to say to the world, and much more importantly, to each other that this is the land of the free except for the Negroes; that we have no second-class citizens except Negroes; that we have no class or caste system, no ghettoes, no master race except with respect to Negroes?

Now the time has come for this Nation to fulfill its promise.

That was 57 years ago.

Kennedy was certainly right to proclaim the Constitution’s clarity on the subject. After all, the immediate aftermath hadn’t just produced 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the United States Constitution. Added in 1868, the 14th Amendment in particular created the legal framework for equality and justice for all in the face of action by some states to deny it to the newly freed slaves. The intent of the authors of the 14th Amendment had been to “incorporate” the federal protections afforded by the Bill of the Rights against the tyranny of the states. As Section 1 reads:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Yet it took JFK’s assassination and Lyndon Johnson’s landslide victory in 1964 to make passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 possible. Those laws made the 14th Amendments guarantees of due process and equal protection of law real in the lives of millions of Americans.

And yet, those gains remain tenuous. In 2013, after all, Supreme Court struck down the “pre-clearance” provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a move which immediately triggered the disenfranchisement of millions of voters in GOP-dominated states. The late Antonin Scalia wasn’t content to brand the VRA as a “perpetuation of racial entitlement”; he argued in favor of striking down affirmative action laws because the 14th Amendment wasn’t “only for the blacks.”

But as we fast forward to the hundreds of thousands of Americans of every race, ethnicity, gender and sexual identity now marching in cities around the nation, the question could fairly be asked if the 14th Amendment even applies to African Americans. As the growing body count shows, the lives of black men and women of all ages remain subject to the judgments of individual police officers and the whims of white bystanders. After all, a teenage Trayvon Martin can be killed by an overzealous neighborhood watch “volunteer” and a 22-year-old John Crawford shot dead by police while holding a BB gun for sale in a Walmart store, all without consequence for those who took their lives. In Cleveland, 12-year-old Tamir Rice was slaughtered while playing with a toy gun in a local park.

Where was due process and equal protection for them? Does a police officer shoot Tamir Rice within two seconds if the child had been white? Would a neighbor have even called the police in the first place?

To ask these questions is to answer them.

To answer them honestly requires changing police practices, changing laws (like those around “qualified immunity” for police, and perhaps hardest of all, changing ourselves.

But that challenge—expanding the circle of the American community to truly include all of us—is the great unfinished work of the nation’s founding. The events of recent weeks—the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd—make neutrality in the face of persistent injustice an untenable and shameful position. While looting and destruction cannot be tolerated, they are but symptoms of the disease. As Frederick Douglas put it in 1866:

“The thing worse than rebellion is the thing that causes rebellion. What that thing is, we have been taught to our cost. It remains now to be seen whether we have the needed courage to have that cause entirely removed from the Republic.”

To put it another way, we have reached a time for choosing, once and for all. When American demand “justice for all” and insist “black lives matter,” they are making clear which side—and whose side--they have selected. In 2020, it is past time to update Ulysses Grant’s 1861 declaration:

“There are but two parties now, traitors and patriots. And I want hereafter to be ranked with the latter and, I trust, the stronger party.”

The hundreds of thousands of Americans in the streets standing for racial justice and the millions more supporting their cause are the patriots. The righteousness of their struggle, embodied in the 14th Amendment, is “as clear as the Constitution.” But refusing to deny due process of law and equal protection of the laws to black Americans isn’t just a question of statutes and enforcement. As JFK put it in 1963, “we are confronted primarily with a moral issue.” At its most fundamental, it is the question Lebron James asked on Twitter on May 31, 2020:

“Why Doesn’t America Love US!!!!!????TOO”

It will a glorious new dawn for the United States when black Americans don’t have to pose that heartbreaking question and can see and feel that love in their lives and the lives of the families, friends and neighbors. But that can never happen if we must continue to mourn the next George Floyd, Philando Castile, Eric Garner or Abraham Franklin, all killed “for no offence but that of negritude.”

NOTE: I would like to apologize for the use of some archaic language and painfully explicit descriptions in what follows. Difficult as it is to read, I believe it helps highlight true horrors in our past that Americans must confront.